Gold standard

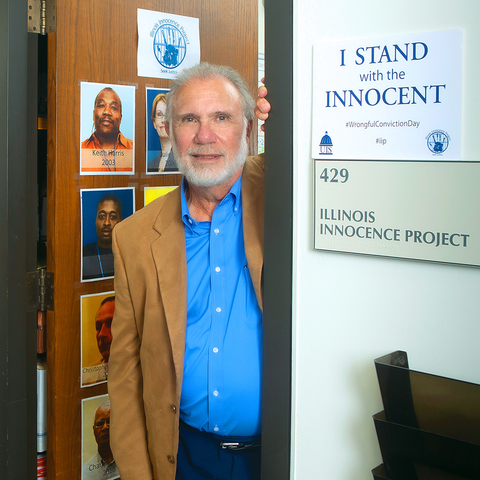

Professor Emeritus Larry Golden—who has been with SSU/UIS from the start—reflects on building a university from scratch and bringing justice to the wrongly convicted

I was the youngest faculty member hired when Sangamon State University opened in 1970. I am the last of the founding faculty members who is still here in a formal role. The 50th anniversary of the University is also my 50th anniversary of teaching here.

Most of my work has focused on the law and issues of racial, economic and gender inequality. The late 1990s were the beginning of a movement to investigate cases of people who had been convicted and sentenced to death, but who might be innocent. This was primarily prompted by the advent of DNA research. It was the first time the existing evidence in these cases could be tested and used to prove innocence, and perhaps lead to the actual perpetrator.

That was the beginning of the Innocence Movement, which today is one of the most significant movements in American history with regard to the criminal justice process. It feeds directly into what our country is facing right now with the current unrest over police misconduct. Innocence cases throughout the last 25 years have exposed systemic misconduct by police, prosecutors and even judges, misconduct that has resulted in innocent people being convicted for major crimes and put in prison for the rest of their lives.

In 2001, we began to teach a class in the legal studies department with our senior students, asking them to work with lawyers on cases that might result in a finding of innocence. We continue to offer a class every semester on wrongful conviction.

We are the only undergraduate university in the country that hosts an Innocence Project. Students from disciplines across the University participate in our work. We put great faith in our undergraduates to help the lawyers as they are doing their job. The amount of research that goes into any of these cases is immense—the gathering and reading of transcripts, the identification of evidence. That’s the primary work that students—as interns, volunteers and workers—do after staff members screen cases. We get approximately one request a day for help—around 340–350 requests a year. Since 2011, we’ve been able to help 14 people get released from prison because they were innocent.

The first case I spent time working on involved Julie Ray of Lawrenceville, Ill., who was convicted of killing her 10-year-old son. Other than the fact that she was in the house with him at 3 a.m. when he was brutally killed, there was no evidence at all that would pin the crime on her. Eventually, it was shown that a serial killer who had been traveling through the area was responsible. In 2006, Julie had a new trial and was found innocent. But it really ruined her life.

Because of the way the criminal justice process is set up, once a person is wrongly found guilty, it takes years to reverse that finding. Even with good evidence, it takes a long time. The presumption is that these people are guilty, not innocent. Our cases are rarely solved. The average case takes three to four years from the time we start work.

Getting someone who is innocent out of prison—it’s almost impossible to describe what that means, to be able to give back some part of an individual’s life. I’m not a terribly religious person, but the only word I’ve been able to come up with to describe it is “blessing.”

The founding of the University has been incredibly important in my life. I wouldn’t give up those few years for anything. When I came here in 1970, the campus was a mud hole. There were no departments. There was no policy. There was no curriculum. We all were just arriving and starting to develop classes. It was an exciting group of faculty—folks coming out of the 1960s, many of whom were socially active in a variety of ways and most of whom had a vision of helping to build a university that would be important for us, for the nation, for the state. Very few people have had that kind of opportunity, to build a university from scratch. Literally. We had to put together a curriculum; we had to put together policy. At that time, we had no tenure. It was just a wing and a prayer and we were off.—As told to Mary Timmins

Edited and condensed from an interview conducted on July 28, 2020, with Larry Golden, professor emeritus of political studies and legal studies, and founding director of the Innocence Project at UIS