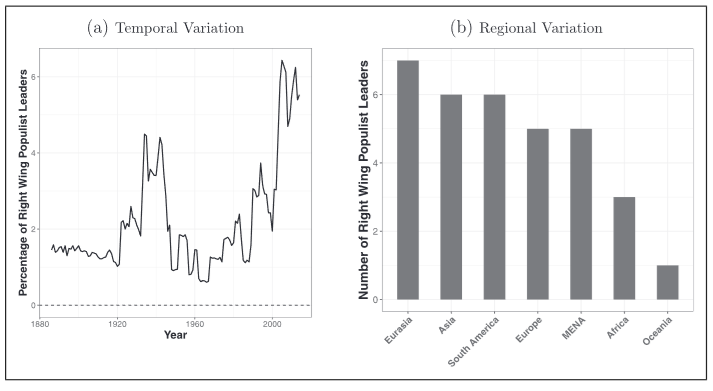

Right-wing populist leaders have been at the helms of governments in all regions of the world, but they have taken power in an increasing number of countries in recent years. In fact, the percentage of right-wing populist leaders in the world in the past decade has surpassed that of the World War II era, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Domestic economic frustrations cause many people to blame those perceived as “outsiders” for their woes, leading to anger against migrants, global elites, and institutions that promote economic interdependence. Right-wing populist ideologues seize on these grievances, using rhetoric that emphasizes a common message regardless of the country: that their nation is a victim of global governance and foreign “others,” that it must take revenge on these enemies, and restoring national status will require aggression and violence. Rhetoric commonly used by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, former U.S. President Donald Trump, Prime Minister Modi of India, and former President Duterte of the Philippines embody these trends. But does this hyper-nationalist, anti-globalist rhetoric from global leaders actually lead to more international disputes? Does this exclusionary, grievance-based tough-talk cause military aggression, and can democratic institutions restrain these leaders from starting armed conflicts?

My colleagues from three different universities and I recently published a study in the Journal of Conflict Resolution that reveals a surprising and disturbing trend given the recent rise of right-wing populist leaders: leaders that use this hyper-nationalist, anti-globalist, revenge-oriented rhetoric are indeed more likely to initiate militarized disputes against other countries, but only if they are leaders of democracies with active civil society engagement in government. Put differently, right-wing populist dictators don’t always follow through with their tough-talk, but elected right-wing populists in democracies with varied opportunities and associations for direct participation in government like the United States really do start more conflicts.

The reason, we argue, is simple: dictators can rail against global elites and institutions and perhaps threaten military aggression against “outsiders” to enhance their “strongman” image, but sometimes this is just cheap talk, and they face little political pressure to actually follow through by starting what might turn into a costly conflict. But the rhetoric used by right-wing populists—blaming outsiders for national decline, declaring a need for vengeance to restore national glory, and promoting the use of military force to achieve it—has real psychological effects on domestic citizens’ attitudes toward that leader. According to evidence from our survey experiments conducted in India and Japan, campaigning on this rhetoric boosts confidence in that leader among all constituents, not just right-wing partisans.

This type of messaging can help leaders get elected by appealing to our fears and frustrations, but it also disproportionately galvanizes civil society groups that then put constant pressure on the leader to follow through or face electoral punishment. Even when this rhetoric is all a bluff, solely meant to gain domestic popularity, integrated democratic institutions will make it harder for the right-wing populist leader to back down from their own messaging. The consequence is an increased probability that right-wing populist leaders in participatory democracies initiate military conflicts against other countries, which we find using an original dataset of right-wing populist leaders around the world from 1886-2014. Given the increasing frequency with which these leaders are coming to power in the world through democratic elections, we expect to see an increase in international conflict if this trend continues.

Of course, we certainly do not advocate dictatorship as a prescription for global peace. There is a considerable body of evidence for the democratic peace – that democracies rarely, if ever, go to war with one another, even if they do sometimes go to war against non-democracies. But we are left to wonder why people from across the ideological spectrum seem to respond so positively and uniformly to hyper-nationalist appeals, and why this rhetoric increases confidence in the leader that espouses it.

To the extent that populism in general emphasizes “us” vs “them,” right-wing populism seems to have a rhetorical advantage over left-wing populist and non-populist rhetoric with respect to motivating domestic constituencies. It appeals to anger, a highly visceral emotion, which may aggravate the more aggressive passions that make up the human condition. When this translates to votes, right-wing populists get elected. And in participatory democracies like the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and many others, citizens get what they ask for. These countries have propped up the current global order, which, for all its faults, has been the source of the lowest rate of international conflicts since the creation of the modern state system. But due to the apparent power of reactionary and exclusionary rhetoric, citizens in highly participatory, democratic societies concerned about increases in militarize conflict in the world will need to continually look inward to find their source.

You can read the full article, Right-Wing Populist Leaders, Nationalist Rhetoric, and Dispute Initiation in International Politics, by Dr. Minnie Joo (University of Massachusetts Lowell), Dr. Brandon Bolte (University of Illinois Springfield), Dr. Nguyen Huynh (Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo), Dr. Vineeta Yadav (Penn State University), and Dr. Bumba Mukherjee (Penn State University), for more details.

Author:

Dr. Brandon Bolte is an Assistant Professor in the School of Politics and International Affairs at the University of Illinois Springfield. Beginning July 1, he will also be a member of the Board of Directors of the World Affairs Council of Central Illinois. Dr. Bolte received his PhD from Penn State University in 2022, where he was subsequently a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow and 2022-23 Peace Scholar Fellow with the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). His scholarship on civil wars, militia groups, international conflict, and quantitative methods can be found in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, International Studies Quarterly, The R Journal, and Mathematics.