I write on this blog often about the importance of news literacy – being able to detect misinformation and bias in the news coverage you consume.

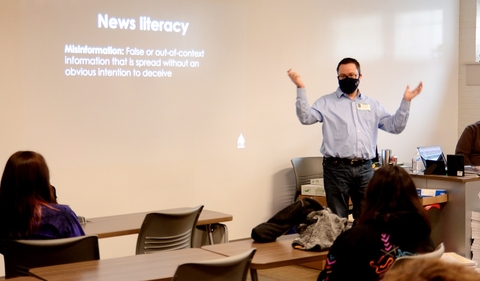

I recently had a chance to present that message to a younger audience: a group of high school juniors and seniors at my alma mater, La Salle-Peru Twp. High School in La Salle, Illinois. My high school classmate, college roommate and good friend is a social science teacher there and invited me to speak to three of his classes.

It’s great to see my friend is ahead of the game on implementing a new state law that requires all public high schools in Illinois to include a unit about media/news literacy into the curriculum starting with the 2022-2023 school year. Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed House Bill 234 over the summer.

As the last several months have shown us, misinterpreted or flat-out bogus information about vaccines, masks, the outcome of the 2020 presidential election and much more affects – and polarizes – all ages.

So I thought I’d take a moment to provide a condensed version of my media literacy presentation right here.

Check your feelings: If headline or social media post makes you feel something – angry, sad, anxious, disbelief or even a big LOL – check that feeling. That’s a decent sign that what you’re reacting to isn’t completely (or at all) true.

Do a little digging: If you doubt what you’re seeing, dig into these three questions:

- Who is behind the info? Is the source a legitimate, trusted news outlet? Or is it your Facebook friend who is sharing their unresearched, unsubstantiated theory on today’s news?

- What’s the evidence? A well-researched piece of information should have clear, identifiable sources – either people who have the credentials to know what they’re talking about or other articles from reputable sources.

- What are other sources saying? It is highly unlikely that your Facebook friend I mention in question No. 1 has the exclusive scoop on whatever you’re reading. If it’s a story worth knowing, other media will be mentioning it, either confirming it’s true or giving you reasons it is not to be believed.

To answer all of these questions, you can use a technique called “lateral reading,” which basically means you should open a new tab on your internet browser and start entering keywords about your story to learn more about the source you’re reading, where that source got its evidence and what others are saying about it.

During your lateral reading, you’ll hopefully hit on information from some of my favorite fact-checking websites: FactCheck.org from the Annenberg Public Policy Center; PolitiFact.com, which uses a "Truth-O-Meter" scorecard to rate what politicians say; and Snopes.com, billed as the “oldest and largest fact-checking site on the Internet.”

Once you’ve detected what’s true and what’s false, the next step in a news literacy lesson is to learn how to detect bias.

It’s no secret many news sources cater to audiences on certain sides of the political aisle. The most discussed include Fox News’ lean to the right, and CNN’s and MSNBC’s lean to the left. But what about all of the other sources you consume?

Head over to adfontesmedia.com to consult their Media Bias Chart. It’s a handy tool where you can search for a news source and see where it rates on scales for political bias and reliability. Actual humans review selected stories from a wide array of news outlets to come up with the ratings.

I’m not saying it is bad to read content that leans hard to the right or the left. But it’s important to at least be aware of what you’re reading. And if you find yourself consuming material that is all one-sided, consider seeking out a source from the other side. You might just gain some understanding of how and why your political rivals feel that way about a certain topic. And, who knows, you could actually have a constructive discussion about the topic with someone who disagrees with you, instead of another flame war on social media.

One last tip: Even with reputable news sources, readers often get confused about whether the article they are reading is “news” (a story intended to provide a fair, accurate and unbiased account of an issue) or “opinion” (usually one writer’s thoughts on an issue that will hopefully be – but not always are – rooted in facts).

In a printed newspaper, deciphering news from opinion is easier. Much of the opinion content appears on a page labeled as “Opinion.” On a news website, however, the content is mixed together, with news and opinion headlines appearing right next to each other. So as you’re scrolling through headlines look for labels like opinion, column, editorial, analysis, commentary or perspective to give you a clue that what you’re reading is someone’s own thoughts on an issue. Other clues to identifying opinion content is if the headline of the story (or the title of a TV show you’re watching on a cable news channel) contains the writer’s or host’s name, or if what you’re reading is written in the first person.

I’ll close this post with the message I left the high school students with the other day: You may think your retweet or share of that questionable post is harmless because you’re just one person. But look around, what if all of (or even 10 percent) your friends/followers share it, too? And then those people share it. And then those people ...

The math equation gets out of control quickly and further contributes to the misinformation crisis we face.

Jason Piscia is an assistant professor and director of the Public Affairs Reporting program at the University of Illinois Springfield. He came to UIS following a 21-year career at The State Journal-Register.