Want to know who is going to win an election? Ask the voters!

Out of growing concern about the ability of polling to accurately capture voter intention and “predict” the results of an upcoming election, some researchers have begun to explore a switch from asking voters who they intend to vote for to asking voters to predict the outcome of an election. These are so-called “citizen forecasts.” Voters are asked who will win and what each party or candidate’s vote share of the major party votes will be. Researchers have found this approach to be useful in US presidential elections, with asking citizens to forecast the upcoming election leading to more accurate results than those produced by polling and professional statistical forecasting models.

Researchers claim that asking voters to predict an election result produces a more accurate result than asking them who they will vote for as voters answer the prediction question based their social network and “local knowledge” based on news, their own experience, and historical knowledge…basically a lot of diverse information. In comparison, answering about who they will vote for by its very nature only requires the person think about their own vote choice. The idea is that combining all of this additional information from a large, diverse, group of people making their decisions independently will produce a “wisdom of the crowd.” Another reason may be that by asking people to predict results instead of their personal vote choice, you remove fear of potential judgement from their personal choice, a so-called “shy voter effect”. Indeed, at the presidential level citizen forecasts accurately predicted Secretary Clinton’s share of the 2016 popular vote within .3 points of the actual result, faring better than voter intention questions.

Thinking about all this got us thinking about the ability of voters to predict state elections. Given the increased nationalization of American politics, would voters be able to still accurately predict an election for a state-wide office, which may receive less attention from voters, their social circle, the media, and other sources of all important information? Further, does asking voters to predict election vote shares produce a more accurate prediction than asking them who they are going to vote for or highly complex statistical models that predict elections?

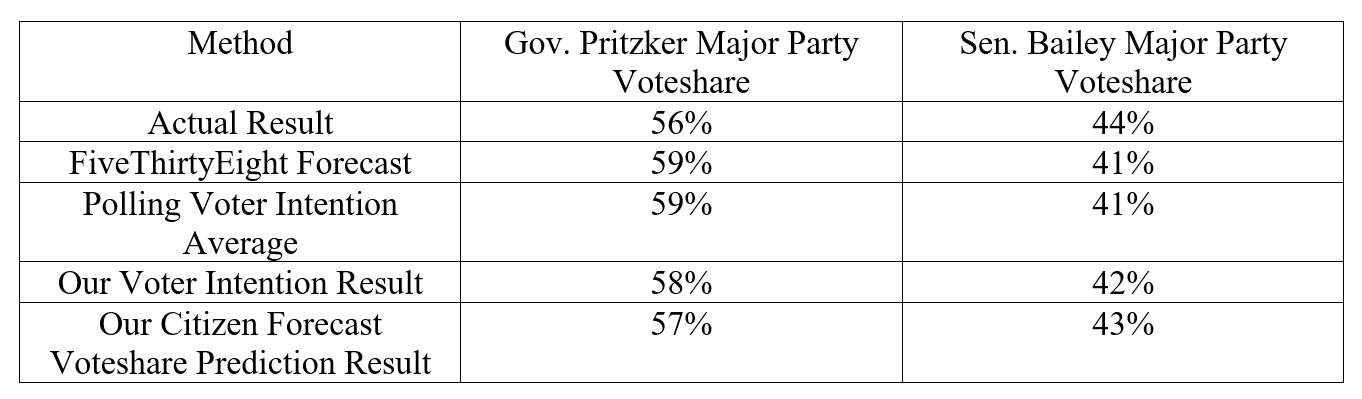

To answer these questions, consistent with additional work in this area, we surveyed 1,000 registered voters in Illinois from October 17th to October 25th. We asked all respondents who they thought would win and what percent of the two-party vote they thought each major party candidate would get for the 2022 Illinois Gubernatorial race, which is their “predicted voteshare.” This last question’s focus on the two-party vote share aligns our work with the research on this topic done in U.S. presidential elections. We also asked registered voters in Illinois who reported they intended to vote in the upcoming governor’s race who they intended to vote for as well. We included quotas for key demographics in our data collection process to make sure our voters accurately reflected the diversity of voters in Illinois. Further, in line with normal practices, where those quotas fell short of our goal, we weighed the data to reflect Illinois voters more accurately (though, thanks to our quotas we had to make minor adjustments, score one for quotas!). The results of our study compared to FiveThirtyEight’s forecast for the election and the average polling result for the major party vote share from non-campaign aligned polls the last 30 days of the race are below (excluding our own intention question).

Our results show that asking voters to predict the outcome of the election was more accurate than 538’s advanced statistical modeling (which uses vote intention polling in it), more accurate than others’ work asking voters their vote intention, and slightly more accurate than our own voter intention question (our team does offer survey research services for any interested party reading this!). Now to be fair, both forecasting models and polling have margins of error, just as the results of our citizen forecast does, and the results of the election are reasonably close to forecasting models and polling considering those types of errors. But citizen forecasting for the 2022 Illinois Gubernatorial election appears to do slightly better at predicting the outcome of the election than other methods. A one or two percentage point may not seem like much, but if citizen forecasts are one or two percentage points more accurate in races like the 2022 Governor’s race in Arizona or Senate race Nevada, that may make all the difference it getting the winner right or wrong.

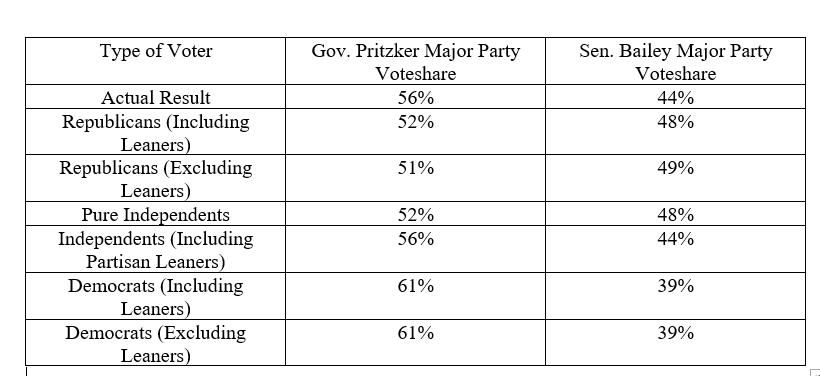

So what groups were more accurate? There is reason to think that partisans may have more biased attitudes than non-partisans due to the way partisanship warps our thinking into being more positive about our given candidate’s performance. Considering the research that has found most independents “lean” towards a party and would be better understood as perhaps more “moderate” partisans we break our data out with self-identified partisans, partisan leaners, and true independents. Below are the average responses of the groups. Turns out “leaner” independents saw the election similarly as partisans, perhaps supporting that view. Further, looking at independents, including leaners, get’s the most accurate result when compared to the election results. We also see partisans consuming a healthy amount of “hopium” and expecting their candidates to perform better than reality.

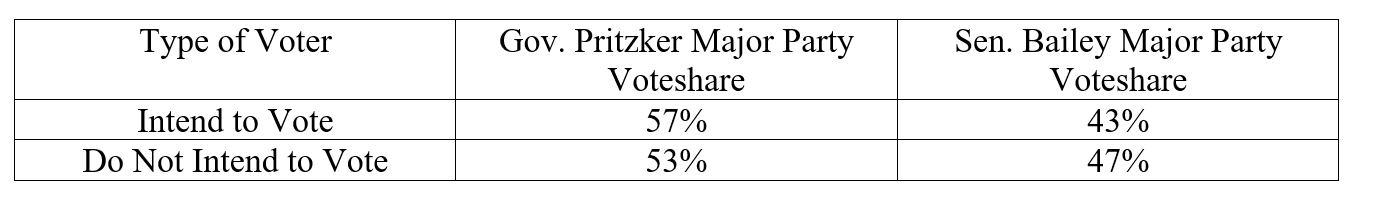

Another reasonable argument is that people who intend to vote in the election may be paying closer attention to coverage of the race and more likely to talk about it with their social network. Put another way, these voters may have more information about the race and produce a more accurate forecast than registered voters who do not intend to vote in the race. Our results suggest that thinking is accurate. Registered voters who did not intend to vote predicted the election to be much closer than it turned out to be and those who intended to vote were pretty spot on.

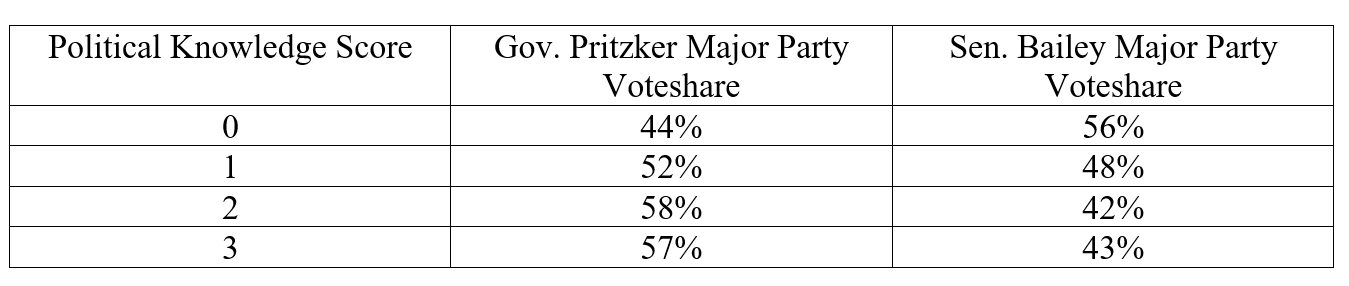

A third set of voters are those who are “politically knowledgeable.” Those who are politically knowledgeable have been found to be more accurate in their predictions of national elections. Those who are politically knowledgeable may have more accurate information about the race given their increased awareness of politically relevant information, particularly about Illinois politics given the race under analysis. To capture political knowledge of survey respondents we asked a series of common measures of political knowledge: who was Secretary of State at the time of fielding (Jesse White, who served in that position for over 20 years), which party held the most seats on the Illinois Supreme Court (Democrats), and which party held the most seats in the Illinois House of Representatives (Democrats) We then took these questions and created a zero to three index of Illinois political knowledge. Turns out, politically knowledgeable voters have more accurate forecasts for the election.

To sum up our findings, the average prediction of a representative sample of Illinois voters produced an accurate forecast of the 2022 Illinois Gubernatorial election than other methods. This prediction more accurately reflected the results of the election than polling voters their voting intention by others and advanced statistical forecasting models, but with a reasonable proximity. Groups that were more accurate in their predictions include: political independents, people intending to vote in the election, and those respondents with a higher level of political knowledge.

We want to be clear that we’re not advocating for eliminating polling voters of their intentions. Asking people who they plan to vote for and asking people to predict the outcome of the election are two very different questions. Voting intention data is deeply useful for understanding what groups of people support certain candidates or policy positions prior to elections. This sort of data helps campaigns refine their messaging and approach and makes them potentially more responsive to at least certain segments of the voting population. Further, with the widespread “horserace coverage” of polls in the media it’s likely these polls are a key piece of information that voters utilize when making their citizen forecasts. So, polling information is useful to campaigns and voters, and also academic researchers like ourselves. For all those reasons, polling to ask people their voting intention should stick around, at least those done by non-partisan groups not aligned with political campaigns.

We recognize and admire the difficult work pollsters do to attempt to get accurate data on voter intentions. We also recognize that our work presented here is on one election in one state and that future work will want to extend this work to other states, or even zoom in to congressional or mayoral elections. You’ll likely be accurate if you forecast that we’ll get to that in the near future. Further, the 2022 Illinois gubernatorial election was not a particularly close election. Would Illinois voters have accurately projected the 2014 Gubernatorial election (decided by approximately 4 percentage points) or the 2010 Gubernatorial election (decided by 1 percentage point)? Also, what about races with more than two competitive candidates, how do voters do with those? That’s all something we most certainly need to unpack as we continue to explore the possibilities with citizen forecasting.

What were your predictions for the election? How close did you get to the final result? Share with us in the comments below!

AJ Simmons is the Research Director of the Center for State Policy and Leadership at UIS. He holds a PhD from the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University. Besides conducting research, he enjoys going bowling and also discussing politics with people he disagrees with.

Nick Waterbury is the Assistant Research Director of the Center for State Policy and Leadership at UIS. He holds a PhD in political science from Washington University in St. Louis. When not thinking about politics, he enjoys spending time on the golf course and traveling an excessive distance to watch sporting events.